Blog

-

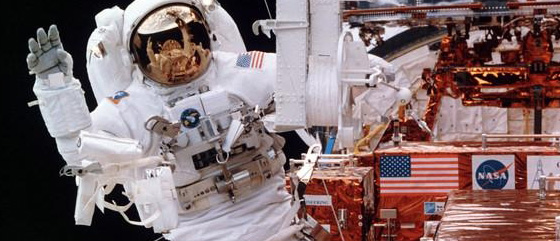

SUCCESFUL REPAIR OF THE MX-1 SAT

FEBRUARY 6, 2023Flattened by a depth of 2.2 microns (roughly equal to one-fiftieth the thickness of a human hair), the outer edge of Hubble’s main mirror was ground to the wrong specification by the contractors who built it, an error called spherical aberration. Instead of focusing incoming light to a single point, Hubble had multiple foci that made the telescope's first images look fuzzy. Once NASA learned of the error, scientists and engineers set out to solve the problem. The Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 (WFPC2) was being assembled at the time. WFPC2 was a backup for the Wide Field and Planetary Camera 1 already on Hubble, and the individuals working on the project were confident they could rework the camera's internal optics to compensate for the primary mirror's error. They added optical components that brought light into focus, counteracting the mirror's flaw in a way similar to how eyeglasses correct vision problems. The installation of WFPC2 during SM1 significantly improved Hubble’s performance and sensitivity at ultraviolet wavelengths. Hubble’s most used instrument for many years, WFPC2 produced more than 135,000 stunning images of the universe. WFPC2 recorded images through a selection of 48 color filters that covered a spectral range from the far-ultraviolet to visible and near-infrared wavelengths. Along with its advanced detectors, WFPC2 also had more stringent contamination control than WFPC1. An L-shaped trio of wide-field sensors and a smaller, high-resolution camera were the heart of the instrument. Astronauts replaced WFPC2 with the Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3) during Servicing Mission 4 in 2009. Today, WFPC2 is part of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum’s collection in Washington, DC.

Read More -

ALIEN SIGNAL DISCOVERY

FEBRUARY 3, 2023Aliens might be able to eavesdrop on Earth from nearby stars, especially as SpaceX sends more satellites into space, a new study suggests. The study determined that radio "leakage" from mobile towers here on Earth is likely detectable from nearby systems such as Barnard's Star (roughly six light-years away), provided extraterrestrials have the right equipment. Such signals are faint now but will likely increase as SpaceX continues to launch Starlink internet satellites into orbit. The study used crowdsourced data of simulated radio signals seen from afar, with data analysis led by Ramiro Saide, an intern at the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) Institute's Hat Creek Radio Observatory north of San Francisco.

Read More